I posit an island, in which three people live: a farmer, a merchant and a banker.

I had been introduced to Take five some time ago.

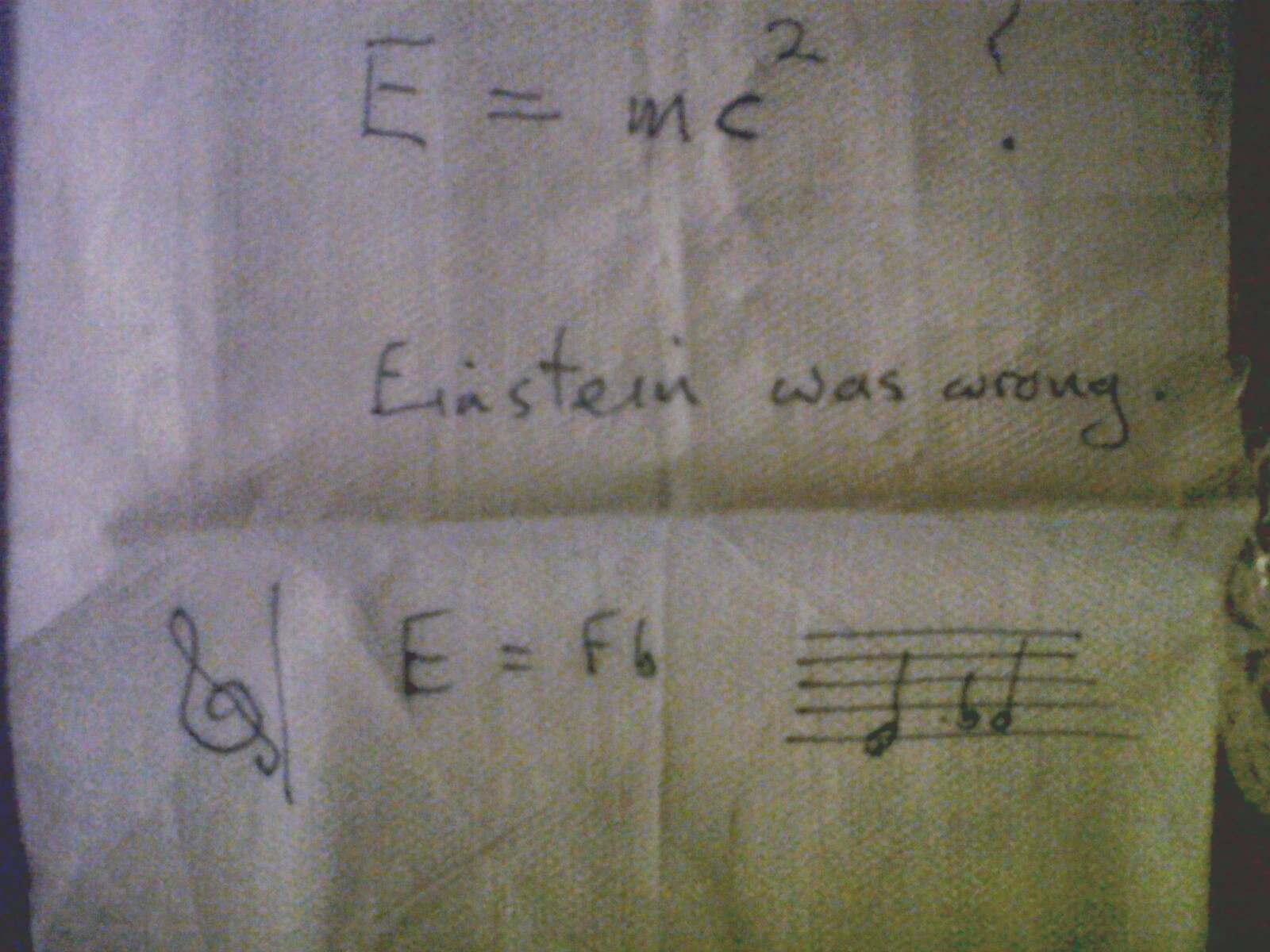

On that former occassion the gentleman concerned wished to know the sum of two digits of two. During his enquiries he called upon a banker but was left somewhat perplexed by the banker’s response.

Take six shows us the consequences of what the banker tried to explain.

The island was located in the warmer temperate regions of the ocean and favoured by typically warm summers and mild winters. The farmer owned fields in the western end of the island which looking towards the favourable prevailing winds brought vibrant and diverse life to that arable and arboreal part of the island. Year on year he diligently sowed his fields, which produced an abundant harvest, which the merchant would take across the mountains to the eastern side of the island which lying as it was in the lee of the winds was much drier than the western side. The banker lived on the western side of the island in a house on a hillside overlooking the sea.

The economy of the island was dominated by this annual cycle, which easily supported the modest lifestyles enjoyed by the island’s community. Both the farmer and the merchant used the facilities offered by the banker.

These three men showed their appreciation to all around by holding annual festivities. The farmer held a festival in the autumn after the first fruits of the harvest had been brought home. The merchant held a ball in the spring to celebrate the end of a trading year, and the start of a new. The banker held a midwinter festival, as he was the only one who could afford both to light and heat a hall sufficiently large at that time of the year.

Over the years the islanders noticed changes in the community. Firstly, the banker moved house, then had his new home rebuilt. Now he was living in a large house with extensive private grounds, including in the western part of the island fenced off areas, which were being converted into a golf course.

None of this was really surprising, the economy was well run; harvests and the profits derived from the trade of the farmer’s produce generated surplus funds with which the farmer and the merchant sought to deal with prudently. Noone however discussed how they did business nor how they managed their own businesses.

The disparity that arose between the banker, the farmer and the merchant however did lead to some serious examination of the mechanisms by which this had come about. Academic reports, and enquiries suggested that far from using money he actually had to support the building of a larger home and the other works being undertaken, the banker had in fact mortgaged his own future earnings thus releasing sufficient funds to pay for all of these things. There was no suggestion that the banker had ever acted without the utmost propriety in this matter however. He had not taken any one else’s money for this and for everything the farmer and the merchant had ever deposited with him he could account in full and all was still available to them.

The farmer and the merchant were not then unhappy with the situation, but as a consequence of the production of the academic papers, and the translation (for that is what really was required) of them into the language of everyday people, they began to wonder whether they really needed to keep such deposits as they had with the banker. If the banker reckoned, and he surely of all people would know whether this was a safe thing to do, that to mortgage his future earnings was good in order to enhance his present lifestyle, then as the saying has it, what is good for the goose is good for the gander.

The merchant was the first to move in this matter and managed to obtain from the banker a significant loan, which enabled him to expand his commercial interests, building a marina on the south coast of the island which would provide easy access to the area near to where the banker was building his golf course, and also to move out of town to what was perhaps inauspiciously described as a lodge near the national park.

The farmer was rather more cautious. He looked at the economics of his situation and concluded that what was safe for him to do would be to no longer finance the annual seeding himself but to seek a loan from the banker to cover that. He used the proceeds to convert several acres of land near to the marina into a golf course. It had become apparent that the banker’s would remain a private affair rather than available to tourists.

All appeared to be well. The world did not end after all of this activity, and indeed everyone appeared to be better off. The construction work had given others skills that they would not otherwise have acquired and provided much needed diversification in the economy. The island acquired the appearance of wellbeing, and the people of the island became quite comfortable with the situation.

Very occasionally the prevailing winds failed to bring the rains on which the farmer depended. Sometimes the dominant winds came from the east. The farmer was aware of this and it was the prospect of this that had held him back from joining the others. But he reasoned that he had survived such years in the past, and having done his sums considered he would be able to do so again.

One such year came upon the island shortly after the completion of the marina. The farmer’s harvest fell short of what was expected. He was only able to repay the banker his loan for planting, by selling all of his seed to the merchant. He knew that this would mean that in the spring he would not only have to borrow to pay for the planting but also to purchase seed to plant. He reasoned with himself that he could afford to do that.

The following spring he approached the banker as usual for the necessary loan. The banker was as ever accomodating, but required a mortgage over the golf course as security for the additional amount. The farmer agreed to the conditions imposed and proceeded with the planned planting programme.

It was a good year, but not quite as good as could have been hoped. The winds had been mixed, and as a consequence of the mixed winds the rainfall in the west was inadequate, but flooding caused much damage in the east. The farmer sold his harvest to the merchant, and repaid most of his loan to the banker. The banker did not require full repayment as he still had security over the golf course, which in any event had a value in excess of the amount of the loan. At this the farmer reflected upon the fact that had he not taken the golf course out of use, his harvest would have been that much greater and he would have been able to repay the debt in full. But he had done so, that was the way it was. The flood damage in the east caused quite some distress, and even the merchant had had to approach the banker for further loans to put repairs into effect. For others it put pressure on goods, some of which fell into short supply and prices started to rise. The price of the farmer’s produce also rose as it too was not as abundant as it had been for many years before. The rising prices however encouraged the banker who only saw increased security therein for the loans he had advanced.

By the time spring had come the price of seed had risen from 130 conche/bushel to 250 conche, such was the shortage of seed. There was also other competition for the seed. It was thought by many that the price would continue to rise for some time to come and seed was seen to be an investment.

The farmer approached the banker for the necessary loan to buy seed from the merchant and to finance the planting. Meanwhile the merchant was was also in discussions with the banker. The merchant and the banker eventually agreed to a mortgage over seed. The merchant would retain sufficient seed to cover twice the amount of his debt to the banker at the prevailing price. If the price rose he would be free to sell off the surplus, providing he also applied some of the proceeds in reducing the debt. If the price fell, he would only need to take action if the cover afforded fell to one and a half times the amount of debt. This did not seem to be an unreasonable solution to the merchant.

It would be a hard year. Food prices continued to rise. The rains were poor in the west, but the farmer had modified his agricultural practice in order to mitigate the effects of lower rainfall and as a consequence obtained a good harvest. The loan on the golf course had to be rolled over again. There was no autumn festival and the winter festival was not as grand as in former years. The people longed for the coming of spring.

The farmer enquired of the banker what he could borrow. The amount available would enable him to buy sufficient seed only if the price were less than 300c/b. The market price was over 350c/b. He approached the merchant, who in a different age may have been willing to help, but the banker’s mortgage over the seed meant that he could not sell for less than the market price, and to have left the difference in price outstanding would have broken his borrowing convenants leading to the immediate recall of all his loans.

In the meantime the banker’s chief steward having noticed the continual steep rise in the price of seed, which he needed in order to feed the household discussed with his master the possibility of entering into forward contracts for the purchase of seed in order to mitigate the adverse risk of fluctuating and increasng prices. He was authorised to enter into contracts up to a maximum price of 450c/b. He put these contracts before the merchant for delivery over the summer.

What now was the merchant to do? He knew that if he gave the farmer what he needed the price would rise over the summer far in excess of 450c/b and he would not in any event have sufficient seed to satisfy the bankers’ order, so he would not be able to accept it. On the other hand, if he accepted the banker’s order the price would likely not rise above 450c/b and he would only have sufficient seed to meet it if he did not accept the farmer’s order. He could sell to the farmer at 300c/b and face ruin, or sell to the banker at 450c/b.

That summer the winds had been just right. No-one could remember a better year than that. The west was properly warm and watered. The east recovered from the previous two wet summers.

The following spring the banker was puzzled. The farmer did not come to him for a new loan. Then it came to him: though the previous year the farmer had approached him for a loan, he had not drawn any of it down. There had been no planting. There had been no harvest. The farmer had instead taken a job stacking shelves in an supranational store, which had been attracted to the island by its recent prosperity.

The merchant had also sold out to the store. The price of seed had risen to peak at nearly 1000c/b, but the wharehouse was now empty.

When the shelves in the store are empty, what then?

Will the deposits in the bank fill the belly?

QI © 2011 QI © 2011 | In 1894 the importance of conserving natural resources was recognized and expressed in a report by the State Fish and Game Commissioner of North Dakota. The report cautioned that short-term thinking and narrow monetary motivations might lead to the destruction of the last tree and the last fish. The following passage shows thematic similarities to the quotation under investigation: Present needs and present gains was the rule of action – which seems to be a sort of transmitted quality which we in our now enlightened time have not wholly outgrown, for even now a few men can be found who seem willing to destroy the last tree, the last fish and the last game bird and animal, and leave nothing for posterity, if thereby some money can be made. |